FASD and the justice system

For some young people with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD), their life journeys are shaped not only by the challenges they face, but by how systems respond to them. Often, the response is not one of understanding, but punishment. We are finding that across the world and in Australia, youth with FASD are significantly overrepresented in the criminal justice system.

Understanding FASD

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder is a lifelong disability caused by exposure to alcohol before birth. It is the most common and preventable non-genetic cause of developmental disability in Australia*. It affects every individual differently but commonly impacts memory, impulse control, emotional regulation, and the ability to learn from consequences. Many also experience sensory sensitivities, developmental delays, and difficulty with abstract thinking, like understanding the time or rules.

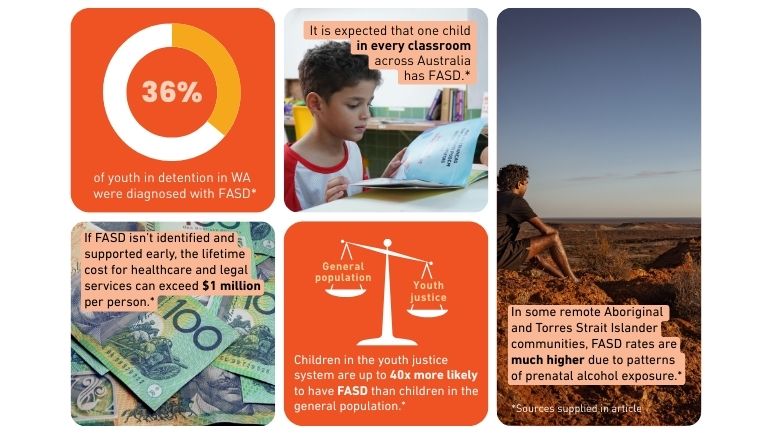

These challenges can make everyday tasks harder. In school, a child with FASD might struggle to sit still, follow instructions, or retain what was said in class just moments ago. They may be labelled “defiant” or “disruptive” when, in reality, they may be overwhelmed or confused. It is expected that one child in every classroom across Australia has FASD.

A system set up to fail

Without the right supports, these young people can fall through the cracks.

- Misunderstood behaviours: A child with FASD might repeat a mistake, not because they’re being purposely disobedient, but because their brain doesn’t retain or process consequences the way others do. In the justice system, this can be seen as “noncompliance” or “reoffending.”

- Trouble understanding rules: Many young people with FASD struggle to grasp abstract rules or legal processes. They might say “yes” to a question they don’t understand or confess just to get out of a stressful or overwhelming situation.

- Sensory overload and impulsivity: High-stress environments, like schools or police interactions, can overwhelm someone with FASD. They may act out impulsively, not out of aggression, but due to a lack of emotional regulation and the inability to pause and consider consequences.

- Gaps in services: Many young people with FASD are undiagnosed or misdiagnosed. Without a diagnosis, they’re less likely to access disability supports, educational adjustments, or therapeutic interventions. Without support, they’re more likely to be misunderstood and therefore suspended, excluded, or criminalised.

As Dr Vanessa Spiller says: “These are young people with a brain injury. And you can’t punish anyone out of a brain injury”.

What the research shows

Studies in Australia and internationally show alarmingly high rates of FASD in youth detention. One Australian study found that 36% of youth in detention in Western Australia met the criteria for FASD, yet the vast majority had never been diagnosed before entering custody. In a lot of cases, these young people have had a history of school exclusion, trauma, out-of-home care, and child protective services. Youth detention became the catch-all for behaviours that systems failed to support earlier on. As the WA study states, “These are missed opportunities for earlier diagnosis and intervention, which may have prevented or mitigated their involvement with justice services.”

What needs to change?

It doesn’t have to be this way. Early diagnosis and intervention are critical. The earlier FASD is diagnosed and recognised, the sooner families and schools can provide supports that can help to reduce frustration and build skills.

- Justice system reform is essential. This includes training for police, lawyers, and magistrates about FASD, adapting processes to be more accessible, and avoiding custodial responses where possible.

- Trauma-informed, neurodiversity-aware supports need to be embedded in schools, youth services, and communities. Behaviour is a way kids communicate, and for kids with FASD, it’s often a cry for help. We need to listen and support them.

- Alternatives to detention, such as therapeutic justice programs, mentoring, supported accommodation, and cultural connection, have been shown to reduce reoffending and improve outcomes.

Shifting the narrative

FASD is a disability and shouldn’t be a criminal pathway. But when it’s misunderstood, ignored, or left unsupported, the risk of coming into contact with the justice system grows. We need to build a society where these young people are seen, supported, and empowered, not just punished for the impacts of a disability they live with.

Please see our other articles about FASD:

Sources:

- Estimating the Prevalence of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder in Australia, Accessed May 2025: https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.14082

- Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) and the criminal justice system: A guide for legal professionals, Accessed September 2025: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S016025272400078

- Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder and youth justice: a prevalence study among young people sentenced to detention in Western Australia, Accessed June 2025: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/8/2/e019605

- Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) and the criminal justice system: A guide for legal professionals, Accessed June 2025: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0160252724000785

- Hopes Australia-first FASD clinical guidelines will increase diagnosis rates, Accessed May 2025: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025-05-13/new-national-fasd-clinical-guidelines/105267916

- *What is FASD?, Sourced June 2025: https://www.fasdhub.org.au/fasd-information/what-is-fasd/