Concussions in children

Concussions in children and young people are more common than we think and often go unnoticed. Unlike visible injuries, the signs of concussion can be subtle, delayed, or dismissed as “just part of the game.” For kids, whose brains are still developing, this can have lasting consequences.

In Australia, concussion is one of the most common brain injuries impacting young people. In 2021-2022 there were more than 17,700 emergency visits and 10,800 hospitalisations for concussion occurred across Australia. Among children aged 10 to 15, over 60% of concussion hospitalisations occurred during sport or recreation, most often when playing AFL or cycling.

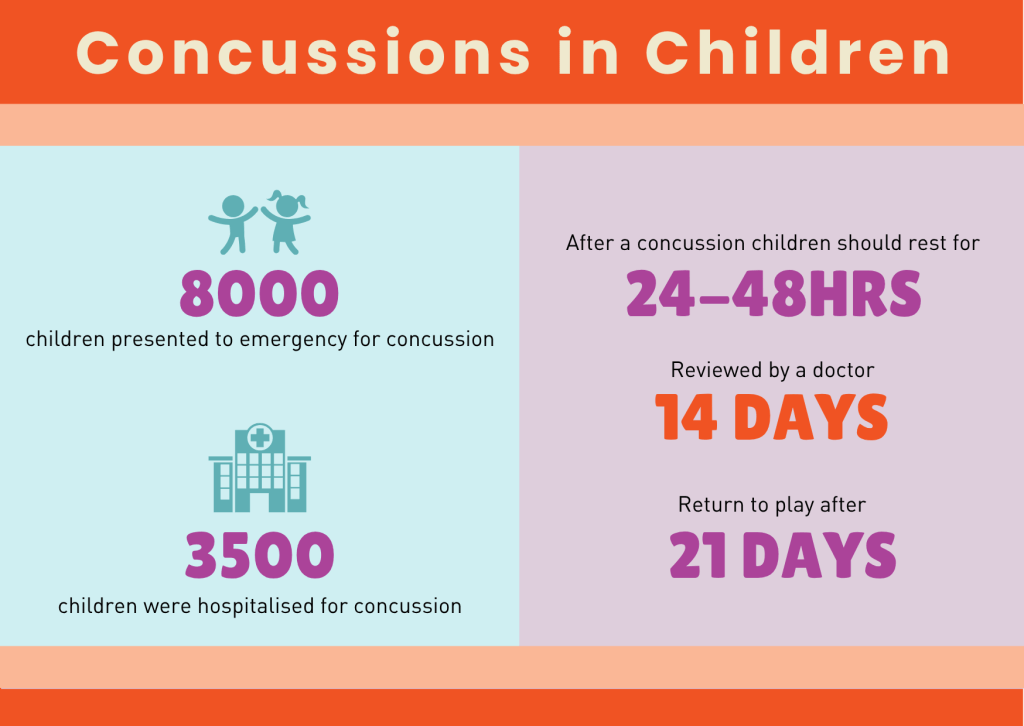

Looking closer there were around 8,000 children who went to the emergency department and 3,500 who were hospitalised for concussion in Australia. Boys made up about two-thirds of these cases, and teenagers aged 13 to 15 were the most affected. Even with the growing awareness that is occurring, the number of concussions happening to young people continues to rise. Many incidents still go unreported or untreated.

Why children are at greater risk?

Children are not just small adults. Their bodies and their brains make them more vulnerable to concussions. Physiological differences such as thinner skulls, less developed neck muscles, and a larger head-to-body ratio mean children absorb impacts differently and less effectively than adults (Van Lerssel et al., 2021). Because their brains are still developing, the effects of concussion can be more significant and longer lasting. This can affect how a child learns, socialises, and participates in daily life.

Inconsistent messages create confusion.

One of the biggest problems is the mixed messages children receive about concussion. On the sideline, one coach might say “you’ll be fine, get back out there,” while another insists on sitting a player out. These attitudes are not limited to kids’ sports. They are also seen at the professional level, where some athletes are praised for “pushing through” despite a head knock, while elsewhere we see strong protocols and medical stand-downs.

This inconsistency leaves kids and parents unsure about what is safe. Too often, they downplay symptoms to stay on the field as they don’t want to let their teammates, coaches or parents. Yet, even for developing brains, even a mild concussion can affect memory, learning, behaviour, and emotional regulation. Research shows that young people hospitalised with concussion are more likely to experience lower academic achievement and further injuries if they return to play too soon.

Coaches need to lead the way.

Coaches are often the first line of defence when a concussion happens. Their decisions matter. Being vigilant means recognising signs, removing players immediately, and pushing for proper medical assessment. The message should always be: If in doubt, sit them out.

By prioritising health over performance, coaches teach young athletes that protecting the brain is part of being a strong, responsible player. The Australian Institute of Sport’s 2024 Concussion and Brain Health Guidelines now recommend at least 14 symptom-free days before contact training and 21 days before returning to full competition. This is a standard that every sporting community should reinforce.

Education for clubs and schools.

Clubs and schools also have a vital role to play. Education programs can give coaches, parents, and kids the tools to:

- Spot the warning signs of concussion.

- Understand the risks of playing on.

- Know when and how to seek medical help.

- Create a culture where recovery is respected.

When schools and clubs model this consistently, children learn to value their long-term health over short-term wins.

Supporting recovery in the classroom.

Concussion recovery doesn’t end when a child leaves the field. It continues in the classroom. For many students, the return to school can be just as challenging as the return to sport. After a concussion, children may struggle with:

- concentration,

- memory,

- fatigue,

- sensitivity to light and noise,

- and slower information processing.

These symptoms can make learning, reading, or even taking part in class overwhelming.

Schools play a key role in supporting recovery by understanding these impacts and adjusting learning expectations while the brain heals. This might include shorter school days, extra rest breaks, reduced homework, or avoiding busy environments like assemblies. One of the most important steps is limiting screen time. Computer work, tablets, and even phones can worsen symptoms and delay recovery.

Teachers, school nurses, and parents should work together on a “return-to-learn” plan, gradually reintroducing mental activity as symptoms improve. According to studies, students recovering from concussion benefit most from flexible expectations, supportive communication, and pacing their workload based on how they feel each day (Lowry et al., 2019; Neelakantan et al., 2020).

By recognising the cognitive and emotional challenges concussion brings, schools can help children recover. Protecting not just their brains, but their confidence and love of learning.

A cultural shift is needed.

A concussion is a brain injury, and kids only get one brain. It’s time for everyone involved in junior sport to deliver clear, consistent messages and back them with action. With stronger leadership, better education, and a united approach, we can help children protect their brains and enjoy the sports they love safely.

“There is no such thing as a good concussion, and we need to be concerned about each concussion and manage each concussion seriously.”

— Dr David Hughes, Chief Medical Officer, Australian Institute of Sport

Innovation can help – but it’s not enough.

Innovative technologies, such as flashing mouthguards being trailed by the Women’s Rugby World Cup team, which light up when a significant impact is detected, are helping to draw attention to potential concussions on the field. These tools could be useful for prompting coaches and trainers to check a player immediately. But technology is only one part of the solution. A flashing mouthguard can’t diagnose concussion, and not every impact will trigger it. What matters most is how adults respond when a child shows signs of injury. Coaches still need to be vigilant, remove players from the game, and push for medical advice.

Education for clubs and schools is essential, so that everyone understands the risks, recognises symptoms, and supports kids to protect their brains, with or without the latest gear.

Concussions are common, often invisible, and always serious. If you suspect a concussion, remove the person from play immediately and seek medical advice. Protecting the brain means protecting the future.

Please see our resources for concussions:

View the QBIC panel discussion at the State Library of Queensland during Brain Injury Awareness Week, which put the spotlight on concussion.

If you have questions or need advice, call the Synapse Information and Referral Line on 1800 673 074. Synapse is here to help with information and support for families, coaches, and clubs.

Sources:

- ABC News (2025). Women’s Rugby World Cup players trialling flashing mouthguards to help predict concussions. Retrieved from https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025-09-10/women-rugby-world-cup-concussion-flashing-mouthguards/105732190

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2024). Concussions in Australia over the last decade. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/concussions

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2024). Injuries in children and adolescents 2021–22. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/injury/injuries-in-children-and-adolescents-2021-22/contents/nature-of-injuries-sustained

- Australian Institute of Sport (2024). Concussion and Brain Health Position Statement and Guidelines. Retrieved from https://www.ais.gov.au/health-wellbeing/concussion

- Australian Parliamentary Senate Community Affairs Committee (2024). Concussions and Head Trauma in Sport Report. Retrieved from https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Community_Affairs/Headtraumainsport/Report

- Australian Sports Commission (2025). Concussion in sport. Retrieved from https://www.ausport.gov.au/concussion

- Bennett, H., Chalmers, S., Fuller, J., et al. (2023). The impact of concussion on subsequent injury risk in elite junior Australian football athletes. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. Retrieved from https://www.jsams.org/article/S1440-2440(23)00069-5/fulltext

- Connectivity (2025). What is mild TBI or Concussion? Accessed September 2025: https://www.connectivity.org.au/symptoms-and-care/what-is-mild-tbi-or-concussion/

- Hopkins Centre (2025). Australian Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Study (AUS-mTBI). Retrieved from https://www.hopkinscentre.edu.au/project/australian-mild-traumatic-brain-injury-study-aus-169

- Lowry, R., Haarbauer-Krupa, J. K., Breiding, M. J., Thigpen, S., Rasberry, C. N., & Lee, S. M. (2019). Concussion and Academic Impairment Among U.S. High School Students. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 57(6), 733–740. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2019.08.016

- Lystad, R. P., McMaugh, A., Herkes, G. K., Browne, G., Badgery-Parker, T., Cameron, C. M., & Mitchell, R. J. (2023). Risk of impaired school performance in children hospitalised with concussion: A population-based matched cohort study. Concussion. Retrieved from https://researchers.mq.edu.au/en/publications/risk-of-impaired-school-performance-in-children-hospitalized-with

- Neelakantan, M., et al. (2020). Academic Performance Following Sport-Related Concussions in Children and Adolescents: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(20), 7602. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207602

- Van Lerssel, J., Osmond, M., Hamid, J., Sampson, M., & Zemek, R. (2021). What is the risk of recurrent concussion in children and adolescents aged 5–18 years? A systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 55(12), 663–670. https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/55/12/663