People say I use brain injury as an excuse because they just don’t understand it

Matthew’s story

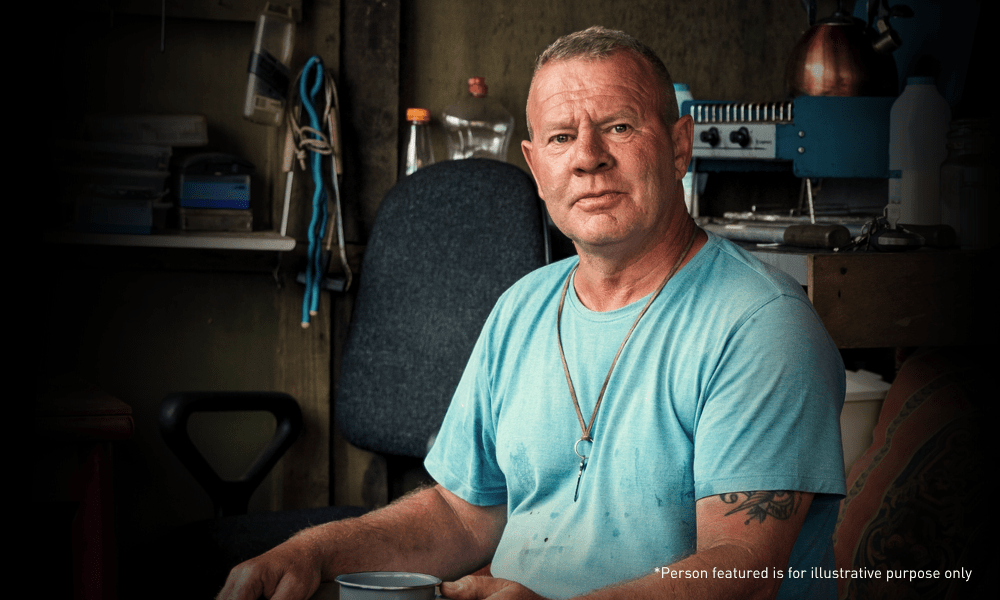

I’m not here to make excuses. I did the crime, and I did the time. Over 10 years of it. But I reckon people should know there is more to my story, not just the headline.

I had an average childhood, things were alright really. Mum raised us right, Dad worked hard. Sure, he’d give us a clip around the ear or the belt if we messed up, but nothing out of the ordinary. I did okay in school. Bit of mischief, but nothing serious.

I reckon it started when I was 19. Out of nowhere, I started flipping out over nothing, couldn’t focus, drank too much. Lost my job, lost the plot. People said I’d gone off the rails. I didn’t understand it myself. I just kept messing up, fighting, stealing, in and out of jail. It wasn’t who I wanted to be, but I couldn’t seem to stop.

The worst part was, I didn’t really understand why I was like that. It’s not like I wanted to hurt anyone. I came from good people, but I kept doing dumb sh*t, acting before thinking, saying the wrong thing, wrecking things.

No one, not the cops or courts, not even me, realised I was living with a brain injury. Turned out I had a bloody tumour in the front of my brain. Only found it in my 40s after a stroke. All those years, no one looked deeper. Even after I blacked out from a head knock and woke up three days later, no one said brain injury. They stuck me in psych, gave me meds that turned me into a zombie.

Living with a brain injury is like trying to follow a map that keeps changing. You forget stuff, lose track of time, get overwhelmed. One smartarse comment and I’d snap. I’d break parole rules without realising, then end up back inside. Again and again.

I’m not saying it excused what I did. I still made bad choices. But it made it harder to stop. It made everything harder. I missed birthdays, my daughter growing up, my mum dying while I was locked up. That stuff cuts deep. People think blokes like me don’t feel anything, but we do. We just can’t really show it.

Last year, I joined a new program that supports inmates and ex-crims living with brain injury. I am learning how to do things differently, so I don’t keep repeating the same mistakes. I’m not proud of everything I’ve done. I hurt people, and I’ve got to live with that. But I also know I wasn’t given a fair shot before; I needed help and I got written off.

I’m not just what’s on my record. I’m someone who had a brain tumour that messed up his life without knowing how to change it. And now I’m speaking up for others with brain injuries. Especially in the justice system, where most of us fall through the cracks. I never thought I could be doing something like that, but it feels good. Like maybe, I could stop someone else getting stuck in the cycle.